The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) protects patient data and imposes strict compliance requirements on covered entities and business associates.

This article explains how HIPAA works and how to understand your compliance position. Explore best practices for achieving compliance, learn about HIPAA penalties, and design the right compliance strategy for your organization.

HIPAA Compliance definition

HIPAA compliance involves following the security and privacy requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Passed in 1996, HIPAA is the main body of regulations for the US healthcare sector.

Compliant organizations must safeguard the Protected Health Information (PHI) of patients. They must secure confidential data against external attackers and internal threats. And they must allow patients to access their records if they desire to.

Key takeaways

- HIPAA compliance ensures adherence to privacy and security mandates. It aims to safeguard Protected Health Information (PHI).

- HIPAA initially focused on health insurance portability. Since 1996, its scope has expanded. HIPAA now addresses digital health records and data protection.

- HIPAA protects individual privacy and provides patient access to records. It standardizes the industry and enforces penalties for violations.

- PHI is a core component of HIPAA. PHI includes crucial data like patient names, addresses, and medical numbers.

- Both Covered Entities and Business Associates that directly or indirectly handle PHI must be HIPAA-compliant.

This article will explore HIPAA compliance in depth. We will look at what Covered Entities must protect. We will learn about the importance of HIPAA regulations. We will also detail the most important compliance areas. The result will be a comprehensive awareness of how to meet your legal compliance obligations.

A brief history of HIPAA

Bill Clinton signed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act into law in 1996. The act sought to streamline the health insurance industry by making it easier for patients to switch providers. The law also sought to cut waste and fraud from the health insurance sector.

At first, HIPAA did not include detailed provisions to protect privacy and data security. But HIPAA changed as the internet expanded. In the late 1990s, healthcare organizations started to embrace digital health records. Moving from paper to digital records created privacy concerns. Digitalization exposed vast amounts of sensitive data to malicious attackers.

Legislators responded by expanding the scope of HIPAA. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) passed the HIPAA Privacy Rule in 2000. The Privacy Rule gave patients greater rights over how organizations used their data. It also extended the right for patients to access health records.

The HIPAA Security Rule followed in 2003. The HIPAA Security Rule added new protections for Electronic Private Health Information (ePHI). Extra provisions described minimum security standards for compliant organizations.

Congress passed the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act in 2009. This act strengthened privacy and security protections. It also provided incentives for health organizations to use the latest IT systems.

HHS then published the Omnibus Rule in 2013. The Omnibus Rule added further elements to the Privacy and Security Rules. It also included requirements about the use of compliant Business Associates.

Since 2013, HHS has made a few less critical alterations to HIPAA rules. The department has published guidance about securing telehealth operations. 2018 guidance also clarified how mental health professionals can share PHI with relatives.

HIPAA is now a wide-ranging collection of rules and standards for healthcare providers. HIPAA rules cover a diverse range of organizations. Covered organizations include clinics, hospitals, and universities. And they also include healthcare clearinghouses and insurers.

The HHS administers HIPAA and publishes regulatory rules. The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) within HHS investigates complaints and possible violations. Violations can result in significant fines. But breaching HIPAA can also lead to criminal prosecution. All institutions handling PHI require a HIPAA compliance strategy.

What is protected health information (PHI)?

The central HIPAA compliance challenge is handling and securing Protected Health Information. Because of this, knowing what qualifies as PHI is crucial. This list includes the most common PHI identifiers. Organizations should protect each identifier with robust compliance policies:

- Names of patients

- Names of relatives or carers

- Dates related to the patient

- Social security numbers

- Addresses

- Phone numbers

- Email addresses

- IP addresses

- Device identifiers

- Medical record numbers

- Health plan numbers

- Fax numbers

- Vehicle or certificate numbers

- Financial details like account numbers

- Facial photographs

- Biometric factors

- Website URLs or other digital identifiers

Data linked to an individual’s identity probably qualifies as Protected Health Information. Organizations must encrypt this class of data. They must limit access and record how employees and third parties use that data. They must also make PHI available to patients when requested.

PHI is also sometimes called Electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI). ePHI includes the same identifiers. But records are digitally stored. Paper and electronic records require different technical safeguards. So, the distinction matters.

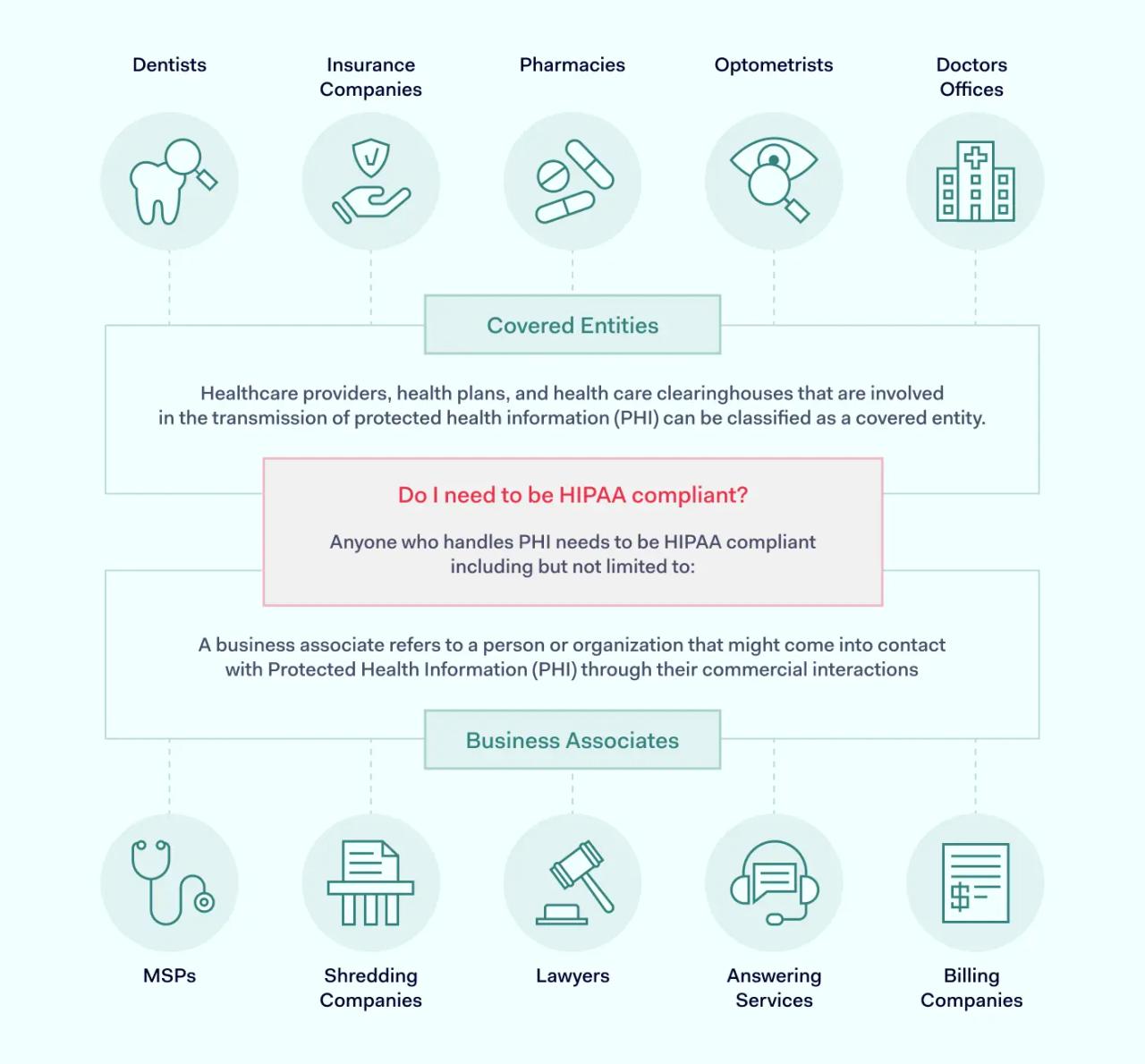

Who needs to be HIPAA compliant?

The issue of who protects PHI can be confusing. Not all organizations connected to healthcare must be HIPAA-compliant. And some organizations only need to cover certain HIPAA rules.

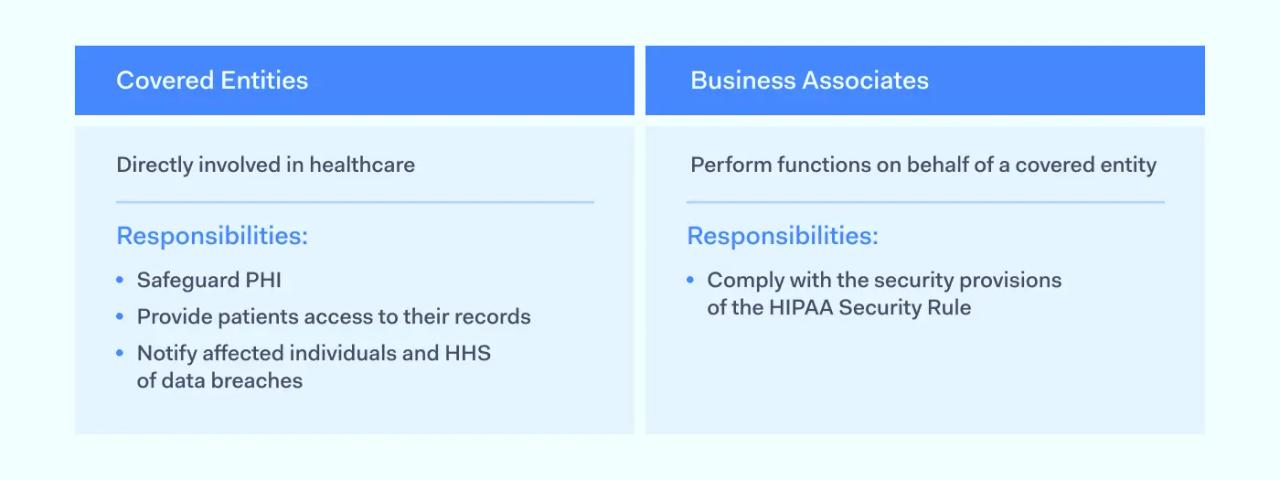

Covered Entities

A Covered Entity is an organization that stores PHI and provides direct services to patients. Covered Entities store or send information regulated by HHS. This makes them liable for HIPAA penalties.

Covered Entities include:

- Health insurance providers that handle claims and link patients to health professionals

- Clinics and hospitals that bill insurers and patients

- Pharmacies or health vendors with access to PHI

- Healthcare clearinghouses

Business Associates

Business Associates are third parties that process or store PHI on behalf of Covered Entities. They generally do not have direct contact with individual patients.

Examples of Business Associates include:

- Cloud storage partners

- Financial support providers

- CRM systems

- Management consultants

- IT technicians.

Third parties that do not handle PHI are not Business Associates under HIPAA. However, companies that sub-contract from Business Associates may qualify.

Business Associates must also comply with HIPAA rules. Business Associate Agreements (BAAs) define the compliance requirements of Business Associates. A BAA must exist before third parties can start working with healthcare organizations.

Organizations not covered by HIPAA

HIPAA does not cover all organizations that provide health-related services. For example, employers may provide health insurance plans for workers. However, they are not expected to meet HIPAA rules.

Lawyers who handle injuries at work, vendors of over-the-counter medicines, and educational institutions are also usually outside the scope of HIPAA. Companies developing fitness apps are also usually excluded. However, fitness data may be integrated into professional healthcare services. In that case, developers would require a compliance strategy.

Why is HIPAA important?

HIPAA performs a range of critical tasks in the US healthcare system. From the patient's perspective, regulations protect individual privacy and secure data from malicious outsiders.

- Health data is attractive to cyber-attackers. Criminals can use PHI to build detailed profiles for phishing attacks. They can steal patient identities, allowing them to file false claims. PHI attackers can also use sensitive patient data to apply for credit cards or loans. HIPAA aims to minimize data breaches and make life harder for digital criminals.

- HIPAA rules empower patients, providing a Right of Access to health records. Individuals have a legal right to see their health data. Patients can check their personal and medical information. They can also suggest changes to ensure that providers have an accurate picture of their health.

- HIPAA rules also include provisions against fraud and health insurance mis-selling. Patients can have confidence that insurers will handle their claims fairly. Corrupt providers are subject to significant penalties or criminal prosecution. This results in generally higher standards of care.

The regulations are also extremely important from the perspective of healthcare providers.

- HIPAA imposes regulatory burdens and applies financial penalties for violations. HIPAA compliance enables providers to minimize their exposure to regulatory and compliance risks.

- HIPAA rules have also standardized healthcare systems across the industry. Standardization makes onboarding new customers and Business Associates easier. Standardized coding and technical safeguards simplify compliance tasks. Healthcare providers benefit from more clarity about designing systems that meet regulatory requirements.

Understanding the main HIPAA laws

HIPAA is a collection of laws and rules. The four most important rules from a compliance point of view are the Privacy Rule, the Security Rule, the Breach Notification Rule, and the Omnibus Rule.

Compliant organizations need strategies to follow all four rules. The next section will explain what each rule seeks to achieve. We will also provide a checklist of critical HIPAA compliance requirements.

HIPAA Privacy Rule

HHS published this section of the HIPAA rules in December 2000. The HIPAA Privacy Rule seeks to protect patient confidentiality. It defines national standards for handling PHI. These standards include guidance about:

- Protecting PHI against deliberate and malicious disclosure.

- Minimizing the risk of accidental disclosure.

- Implementing access controls. Limiting access to authorized individuals.

- Provision of privacy notices to customers. These notices inform patients about how Covered Entities use PHI.

- Applying the “Minimum Necessary” principle when using and sharing PHI.

- Requesting written consent to disclose Protected Health Information.

- Providing the Right of Access for patients to their health records.

- Documenting PHI disclosures.

- Appointing a designated Privacy Officer.

- Training staff to follow HIPAA privacy standards.

- Including privacy requirements in Business Associate agreements.

- Handling complaints about privacy violations.

HIPAA Security Rule

HHS published the Security Rule in 2003. This rule seeks to protect patient data with appropriate technical and administrative safeguards. The Security Rule describes national standards for transmitting, storing, and processing sensitive patient data.

Regulatory requirements of the Security Rule include technical, physical, and administrative safeguards.

Technical safeguards

HIPAA compliance requires encryption of PHI at rest on the servers of Covered Entities and Business Associates. Encryption should protect Protected Information in transit. Multi-factor authentication excludes illegitimate users. Privileged access management restricts access based on user roles. All other health data is off-limits. Organizations should also install threat detection tools. Firewall filters are essential to exclude unauthorized users.

Physical safeguards

Physical controls protect data centers and other devices that store or send PHI. Security measures include locks and surveillance equipment for data storage facilities. Physical security should limit access to storage areas according to professional needs. Data backup servers should also be secure. Incident recovery processes should include ways to access physical devices without exposing data.

Administrative safeguards

This area includes risk assessments that refer to potential HIPAA violations. Companies must create and distribute security policies to all network users. Security officers should train staff to follow those policies.

Disciplinary processes must back up security policies. Logging systems should document access to individually identifiable health information. Security teams should regularly audit HIPAA security controls. They must also create incident response plans to restore systems safely.

In addition to the three areas listed above, compliant bodies must build security into Business Associate Agreements. Covered Entities may suffer penalties if partners operate non-compliant security systems.

HIPAA Breach Notification rule

HHS published the HIPAA Breach Notification Rule in 2009 and updated it via the HITECH Act in 2013. Breach Notification guidelines seek to limit the scope of data breach incidents. They must also inform all stakeholders. Stakeholders include patients and regulators.

According to these rules, a “data breach” involves the exposure of PHI in circumstances that are likely to cause harm to those affected. Harm could be reputational damage following deliberate disclosure. It could also include financial damage from increased cyber security risks.

HHS may not investigate if risk assessments show that the actual risk of harm is low. However, Breach Notification guidelines apply to most data leaks from Covered Entities.

Compliance requirements of the HIPAA Breach Notification rule include:

- Timely investigation of alerts. Investigations should determine whether a data breach has taken place.

- Risk assessments following breach identification. Assessments should analyze the likelihood of data exposure causing harm to affected individuals.

- Notification of affected individuals. Communications must include information about the nature of the breach. They must specify what medical records the breach involves. Breach notifications should also guide the individual about protecting their data.

- If the incident involves more than 500 medical records, organizations should inform HHS. This should occur within 60 days of identifying a breach.

- If the incident involves fewer than 500 medical records, the organization should inform HHS in its annual HIPAA submission.

- Organizations must inform local and regional media outlets if the breach involves more than 500 records.

- Organizations must inform Business Associates of the effect of the breach.

- Organizations must document all breaches, including actions taken in response.

- Covered Entities should respond to incidents by strengthening security controls and processes.

Omnibus Rule HIPAA

Congress passed the Omnibus Rule in 2013. It is known as the “Omnibus” rule because it combines existing HIPAA regulations with the HITECH Act and the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act (GINA).

Congress acted because there was a need to streamline HIPAA processes. The Omnibus Rule reduced the regulatory burden on Covered Entities. Organizations would need to submit less paperwork and carry out fewer regulatory actions. At the same time, the rule strengthened privacy and security regulations.

HIPAA compliance requirements of the Omnibus Rule include:

- Extended responsibility for third parties. The Omnibus Rule expanded the Business Associate definition. Business Associates must now be HIPAA compliant. Covered organizations include downstream sub-contractors that handle healthcare data.

- Limited scope to sell PHI or use health data in marketing. Organizations cannot sell PHI as a product. Organizations must request consent to use PHI in marketing activities and research.

- Higher penalties for compliance violations.

- Very limited use of genetic information in managing insurance plans. Strong privacy protection for customers suffering from genetic conditions.

- Patients have the right to request Electronic Health Records (EHR) in digital format.

HIPAA compliance violations

Regulations have no force without the threat of penalties. Since HIPAA’s start, the Office for Civil Rights has enforced a system of fines. Regulators link fines to factors that include:

- Whether Covered Entities were aware of HIPAA violations

- Deliberate intent on the part of the Covered Entity

- Action taken in response to discovering HIPAA violations

- The number of records exposed by the compliance violation

In most cases, the Office for Civil Rights does not enforce civil financial penalties following HIPAA violations. More commonly, regulators advise Covered Entities to make their systems compliant. Compliance measures could include the adoption of privacy policies. Or they could include the modernization of security controls.

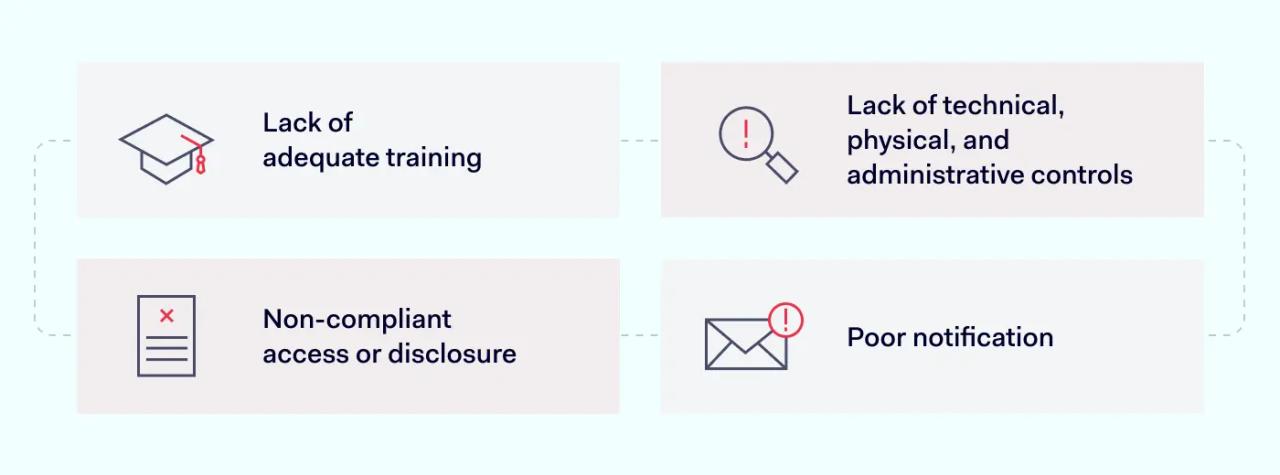

The most common types of HIPAA violations are:

- Lack of adequate training. Employees are not aware of compliant practices. As a result, they expose data and use PHI inappropriately.

- Lack of technical, physical, and administrative controls. Organizations may lack secure encryption. Or they may leave data centers exposed to intruders.

- Non-compliant access or disclosure. Individuals may access PHI without a legitimate professional reason.

- Poor notification. Organizations may fail to notify affected individuals. Or the may not make timely submissions to regulators.

Penalties for HIPAA violations

Under HIPAA law, penalties vary from case to case. But the Office for Civil Rights publishes a fixed schedule of fines. This schedule establishes lower and upper limits. There are four basic tiers, and these categories work as follows:

- Tier 1: Accidental. At this level, Covered Entities are not aware of HIPAA violations. There was no reasonable way they could have discovered the violation. Fines at this level begin at $100 per violation and can rise to $50,000.

- Tier 2: Reasonable cause. Organizations should have discovered the violation. But their compliance systems failed. There is no intent at this level. Organizations do not act with “willful neglect.” Fines range from $1,000 to $50,000 per violation.

- Tier 3: Corrected Willful Neglect. At this tier, the violation was deliberate. However, the Covered Entity took action to fix the violation within 30 days of its discovery. Fines range from $10,000 to $50,000 per violation.

- Tier 4: Uncorrected Willful Neglect. Organizations knew about the violation. But they took no action to remedy the problem within the 30-day limit. Fines at this level range from $10,000 to a maximum of $1.5 million per year for each violation.

Penalties are always higher for larger organizations that expose large amounts of data. For example, the insurer Anthem paid $16 million in 2015 after exposing 79 million records. This represented several Tier 4 findings.

Conclusion: build your knowledge to become HIPAA-compliant

HIPAA compliance is a critical business goal for most healthcare-related companies. Even companies that work in general financial support or cloud hosting services may require HIPAA compliance strategies.

This article has taken a broad approach to the question of what is HIPAA compliance. We have introduced the core components of HIPAA regulations. We have learned the purpose of the legislation and what to expect from HIPAA penalties. But there is much more to learn about this complex set of regulations.

Discover more at the NordLayer Cybersecurity Learning Center. Our library includes comprehensive articles about the HIPAA Privacy Rule and Security Rule. Readers can use our HIPAA compliance checklist tools to check their systems. There are also introductory articles on a wide range of HIPAA-related topics.

Building knowledge is the foundation of a robust compliance strategy. Research your compliance requirements and cut your organization’s regulatory risks.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and not legal advice. Use it at your own risk and consider consulting a licensed professional for legal matters. Content may not be up-to-date or applicable to your jurisdiction and is subject to change without notice.